<< Back

How Researchers Can See Psychosis in Someone’s Eyes

April 08, 2019

The pupil – the dark circle in the center of the eye that flexes in size based on available light – performs a much different role in people with psychosis.

“The pupils are a direct link to the brain. They give away what you’re doing, thinking and feeling. It’s a biological reaction that you can’t control,” said Jimmy Choi, a senior scientist at the Institute of Living’s (IOL) Olin Neuropsychiatry Research Center and staff neuropsychologist at the Schizophrenia Rehabilitation Program. “In psychosis, pupils are used to determine how much of the brain is working to complete a task.”

Choi, bolstered by a National Institutes of Health grant, is the principal investigator of the Neurofeedback Processing Speed Training project studying the use of pupillometry, or the measurement of pupil size and reactivity, in the treatment of patients with neurological conditions like psychosis.

First, he employed a device called a pupillometer to gauge pupil changes as people with psychosis performed cognitive exercises. Then, he used the same tool to see if physical exercise on stationary bicycles had more impact on the pupil size.

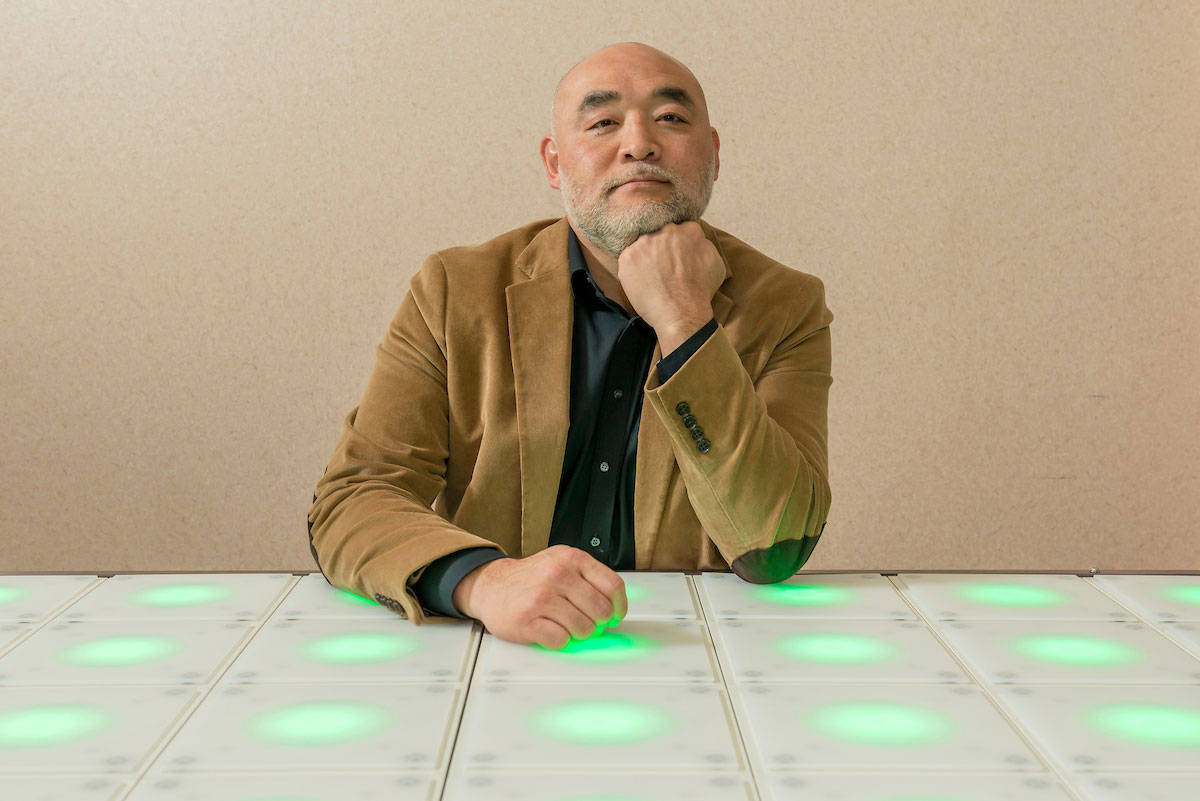

Most recently, he started incorporating a special exergaming board – purchased with $30,000 from the Hartford Hospital Auxiliary — to see if the gamer’s pupils change. The board, about half the size of a ping-pong table, features rows of electronic lights that illuminate in certain orders and at varying speeds. The client stands beside the board and must tap the lights as they illuminate, sometimes tapping multiple times if they flash multiple times. Choi and his research team build an algorithm tailoring the order and speed of the lights based on the participant’s specific cognitive deficit, encouraging the brain to react faster and faster. The team also monitors the player’s heart rate and the speed at which they perform the tasks, in addition to pupil reactions.

The activity, Choi said, helps clients train their pupils to react differently, which can keep the symptoms of their disease in check.

“In psychosis, people’s cognition is severely compromised –memory, attention, problem solving skills. Everything is impaired, including coordination,” he explained. “We look at their processing speed or how fast they’re thinking. The board also forces them to take the whole area into consideration because psychosis compromises the part of the brain that allows them to focus on the whole picture.”

Most clients are encouraged to use the exergaming equipment for two or three hours a week to glean what he called “real world benefit.” Regular use is needed because he said the effects fade after a week.

Study results, which Choi will present later this year at the International Congress of Schizophrenia Research, could be revolutionary in the treatment of people with psychosis, who can often find relief from the voices and other symptoms of the disease with medication but still struggle with cognitive problems.

“If we can improve their cognition, we can get them back into the community. They can go to work or school,” Choi said, noting that gaming also has potential to improve the social functioning of people with psychosis, who often struggle in groups because their minds do not process as quickly as others’. “They always feel a step behind in a conversation. I think this would be much more meaningful to them.”

Looking ahead, Choi anticipates even more ways to use the gaming concept to help people. He has already compared the exergaming cognition results with those of people doing physical exercise to overcome the effects of psychosis in another of his studies, finding that tapping lights on the exerboard improves cognition 32.7 percent faster. The next step, he said, is to compare the performance of exergamers with psychosis with that of those who do not have the disease.

In addition, while clients can currently use an exergaming program on tablets, Choi said he envisions having a smart phone application that makes access much more convenient and portable.

“We’re trying to see if that would help, but it might have something to do with the actual physical movement at the (exergaming) board,” he said. “As a scientist, though, we have to be open to the idea that something might not work as well as we thought.”

For more information on the Institute of Living’s Olin Neuropsychiatry Research Center, click here.